What Is Scrum?

Many ways of organizing project teams, particularly in software development, fall under an umbrella called “Agile”. The idea is that with transparency, communication and buy-in by all members of the team, a project can reach optimal efficiency and productivity. With the data collected during an iteration, the team can identify problems and put forth solutions to fix them.

It’s not a terrible idea. Having a board or card wall, for example, can illuminate where your process might be struggling. A meeting to define work and break it down into actionable chunks is also essential. Regular, quick meetings to verify that everyone has what they need in order to keep working can bring issues to light before they become major stumbling blocks later.

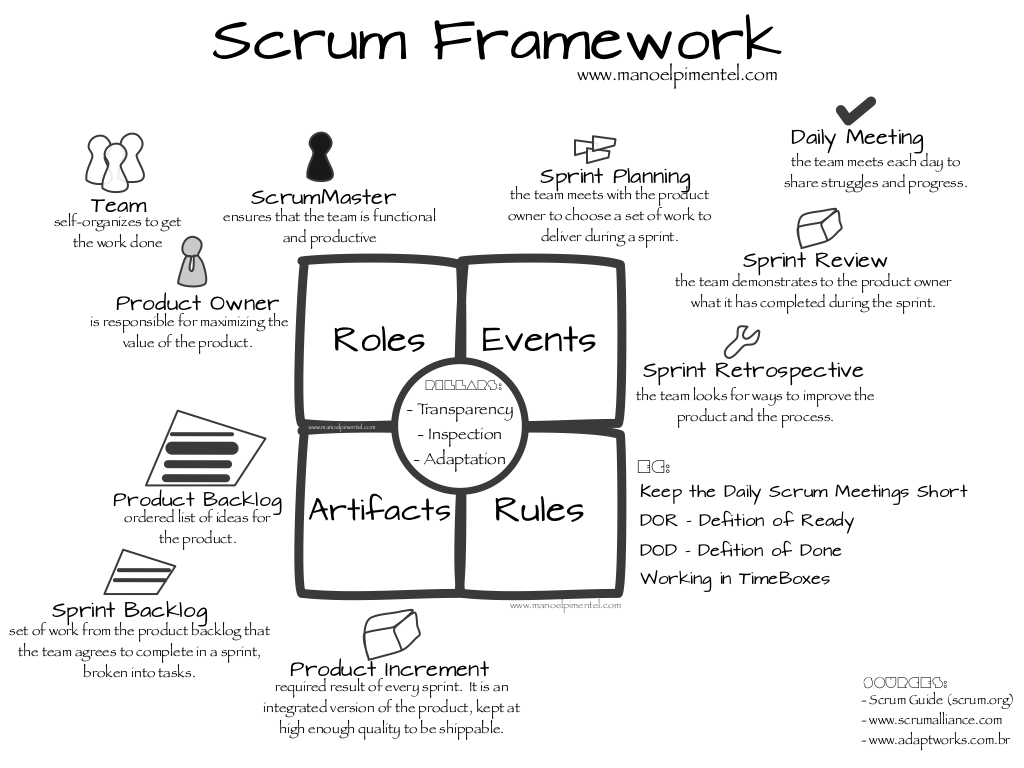

All of these practices can be beneficial to your team if used sensibly. Unfortunately, too many teams (or their managers) decide to use a particular system without much regard for how well it fits any particular project. Since I’ve seen it the most, I’m going to pick on Scrum (no, it has nothing to do with rugby). It’s a form of agile that’s known mostly for its daily, short meetings called Scrums and its timed iterations. It’s most common use, in my experience, is to introduce a vast amount of meetings and structure into a project.

The first step in Scrum is chartering and visioning. Yes, they’re stupid terms. Get used to it. Most of them are. Chartering is an exercise where the team agrees to work together under certain conditions. This meeting requires ridiculously long discussions about things that ought to be common sense. Then there’s a small bit of useful stuff like working hours, role definition and the like.

Next up is visioning, where the product owner explains what the project should ultimately produce. The value of this meeting can vary quite a bit depending on a the product owner’s ability to express his vision. If the product owner can clearly articulate his vision, be prepared to take notes and actually learn something. Otherwise, you’ll want to shoot yourself or play buzz word bingo. The result of this meeting should be a wish list of features the product should have.

After a wish list is created, it’s time to define all the work. To do this the Scrum way, a group of grown-ups sit together in a room to do something called “grooming”. Yes, it’s disturbing. Sorry, they won’t change the name. The wish list is broken down into chunks called stories, which are then broken down into individual tasks. This is not ticket definition. (Well, it is, but we can’t call it that.) Once the stories are defined, the team votes with cards (as if they’re in kindergarten) on how much effort they believe each story to be. This is done in a unit called a story point, which has no bearing on any real life amount of time or effort. More on that later.

Once the stories are estimated in story points, each task gets estimated in time. Again, there is no direct correlation between story points and hours. Ultimately your team will be given a velocity based on story points, which are based on nothing real, which means your ability to do work is some meaningless number at which everyone will smile and nod (Just like the emperor’s new clothes!).

Once all of this is done, it’s time to plan an iteration. An iteration is a set period of time, usually two weeks, in which you work on the project. The time scale is not tied to anything. It has no value whatsoever except to give management a sense of your velocity as a team. Yes, another stupid term. It basically tells those in charge how much stuff you can do in a certain amount of time so they can plan things. And we accept this even though the unit of measure doesn’t correspond to any real amount of time or work.

Finally, you divvy up the tasks and send people off to work. You’ve spent perhaps two or three full days in meetings to accomplish all of this. Now you can finally work. But don’t get too excited. Every day, you’ll be interrupted by a meeting in which the team meets to listen to each member tell what he did yesterday, what he’s doing today and if there’s anything preventing him from moving forward.

Finally, after two weeks (well, minus all the meetings to plan things), you have finished the sprint. You may or may not have finished the work. That doesn’t matter. Our calendar says the sprint is done. There may or may not be a demonstration at that point. Either way, you will have a review meeting and a retro meeting where you discuss with two different groups what went right, what went wrong and what you can do better.

Now you can start all over again, but without the chartering and visioning.

What’s wrong with this process? Look how much explanation it just took. And that’s not even a full explanation. There’s far more detail to the process. A lot of work has been added. And have you gained anything? Who knows? You weren’t measuring anything in story points before. You’ve also needlessly introduced yet another set of vocabulary.

So Is Agile Bad?

No. Agile, as its name would indicate, is a good idea. Anyone who has worked on a software project before knows that things will change no matter how carefully a project is planned. Your project must be able to adapt. Things will get lost in the shuffle if there are not mechanisms for communicating them regularly. The agile concept addresses this problem. However, an overly formalized approach gets in the way more than it helps.

Estimating a story with points and then determining a team’s “velocity” based on its average number of story points completed is silly at best. More importantly, why should you care about timed iterations and velocity in the first place. Wouldn’t it be better to define what you want done next, then do it. Estimate in real hours and then learn from your over/under time. It’s more important that people are working and that they have what they need to do their work.

Transparency, communication and accountability are the most important pieces. A simple kanban board, for example, provides this. It makes everyone aware of what’s working and what’s not. Rather than imposing arbitrary structure up front, it provides a view of the process, and problem points can be addressed as needed. Scrum imposes structure, then promises (but rarely delivers) the removal of cruft after a few sprints. Scrum runs the wrong direction. You should start with one piece, then add more as necessary, not the other way around.

With a simpler system, you can continually evaluate your processes and change them as needed. With Scrum, you’re continually stuck with a large set of processes and meetings that you’ll probably be stuck with indefinitely whether you like it or not.

Leave a Reply